Vital Signs

Vital Signs

Ask any acute care nurse working 16-hour days, long-term care nurse working short, or community nurse with an overwhelming caseload, and they'll tell you that health care is a numbers game.

But they're not talking about the numbers marked on the barrel of a syringe, or the number of pills on a med tray. One of the biggest issues of concern for working nurses today involves the number of workers available to provide the care Canadians need and expect.

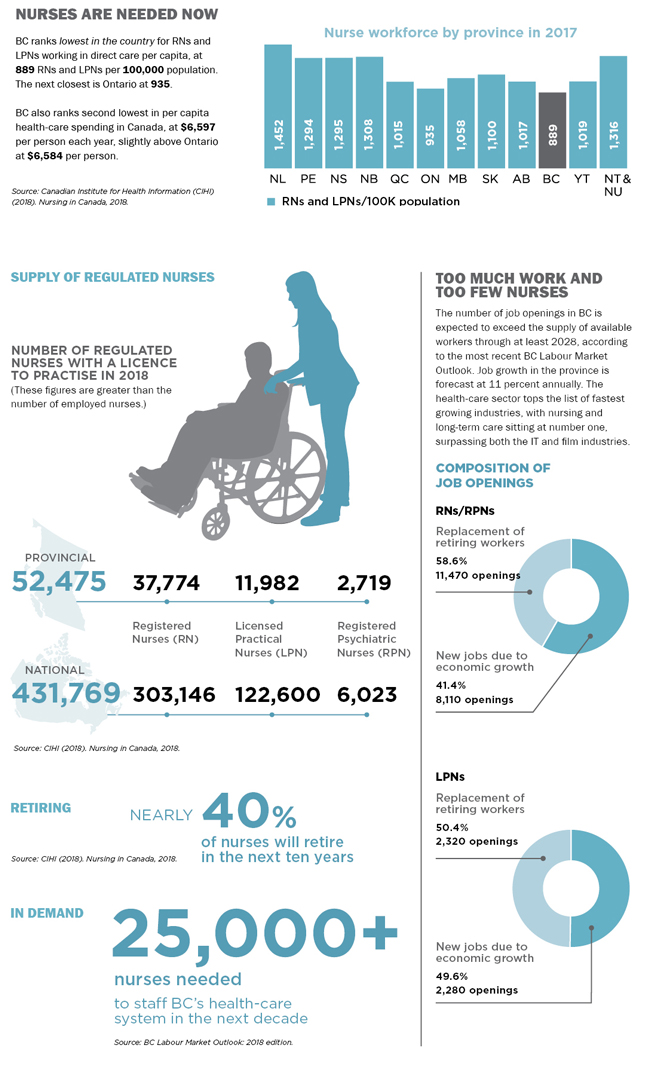

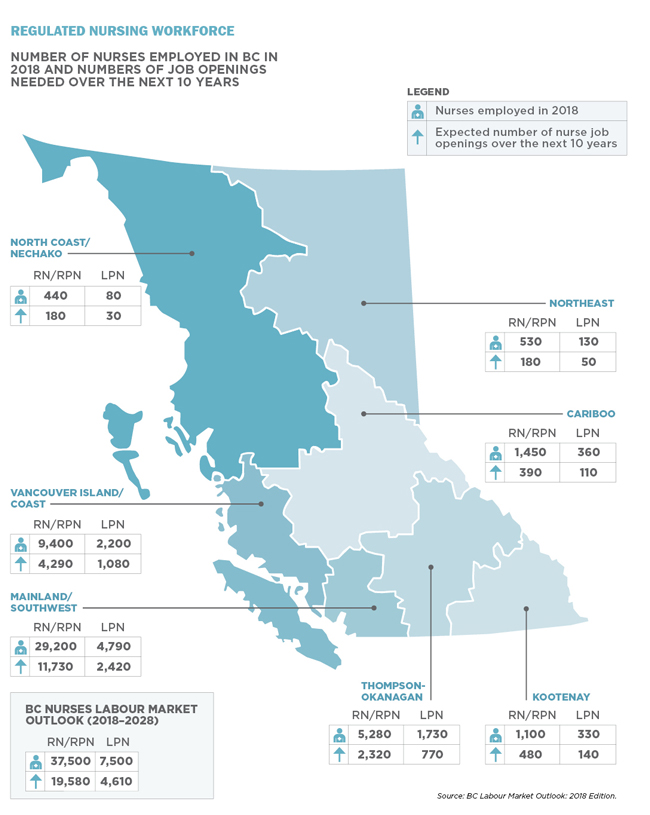

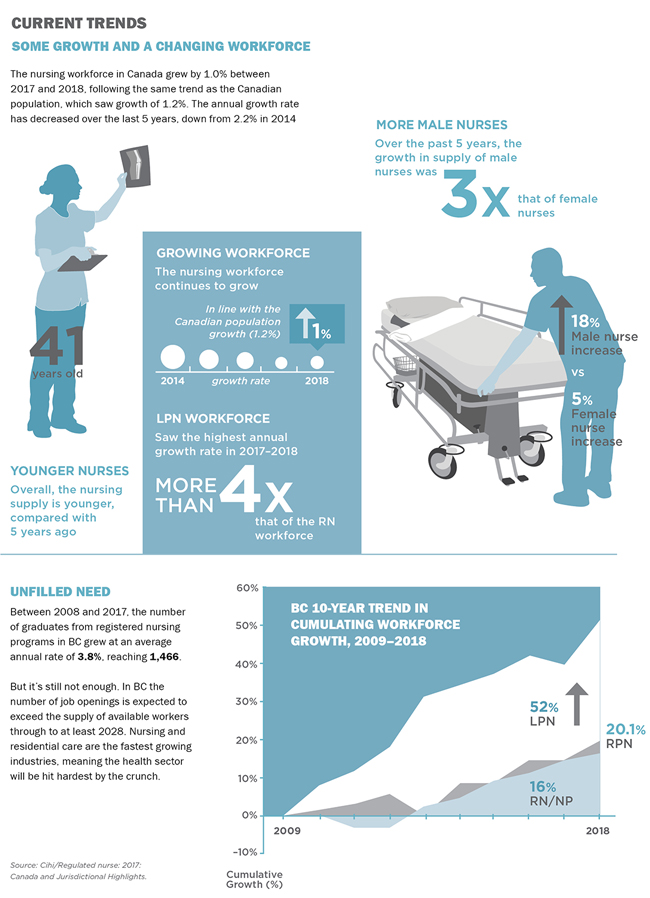

There is a looming demographic crisis facing almost all sectors of the economy. Acute labour shortages are opening up as a generation of baby boomers retires. In BC the number of job openings is expected to exceed the supply of available workers through to at least 2028. Nursing and residential care are the fastest growing industries, meaning the health sector will be hit hardest by the crunch.

For nurses, this forecast is a perfect storm of growing health-care demand coupled with a dwindling supply of health human resources. If serious action isn't taken, nurses can expect to work longer hours in worsening practice conditions, all the while caring for an aging population with growing acuity.

It's clear that planning and investments are needed now. The health-care sector is as vital to the economy as any other industry. And the health-care workforce is not just an expense, but an economic driver that enables productivity and prosperity in every corner of the country.

Over 1.5 million people work in Canada's health sector and 70 percent of all direct health-care costs go to labour – the majority being nurses. According to official statistics, there were 431,769 regulated nurses in 2018 – at a cost of more than $150 billion a year.

And still there are not enough.

It's a global problem. The World Health Organization estimates that within a decade we will be short some 18 million health-care workers worldwide. The US will be short one million nurses and over 100,000 doctors – and luring Canadians south as a result.

Canada in turn will increasingly look beyond its borders for educated health-care workers. Today, one in four are now internationally educated.

LISTEN TO NURSES

For years, BCNU has been working constructively to help address the crisis. At the bargaining table we've secured employer commitments to create thousands of new regular nurse positions in all health-care sectors and provide existing staff with paid education to work in specialty nursing positions.

We also understand the challenges of rural and remote recruitment and negotiated dedicated funding to address the staffing needs of remote communities. This has helped fund grants for such things as tuition relief, loan forgiveness and housing assistance to help make these jobs more attractive to nurses.

Most recently, BCNU negotiated detailed contract language to encourage managers to staff units appropriately and avoid the use of overtime. This kind of systemic change has the potential to save hundreds of millions of dollars that could be invested in new nurse positions and help reduce the toll on nurses' health and well-being.

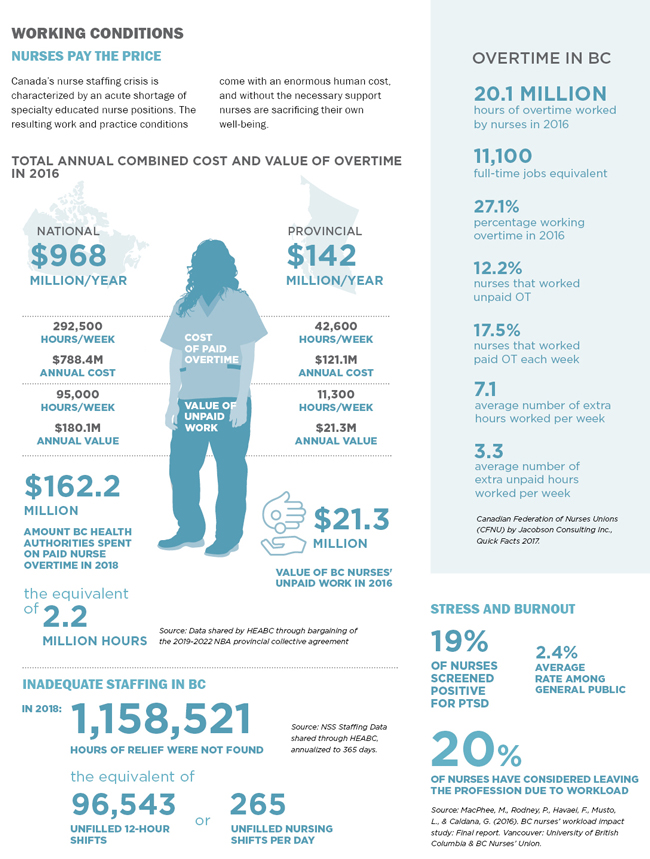

OVERTIME IS NOT THE SOLUTION

The scale of Canada's nurse shortage is masked by employers' chronic reliance on overtime to keep hospital wards staffed. It's an unfortunate practice that's not unique to BC.

It's also a costly, vicious circle driven by the acute shortage of specialty-educated nurse positions, such as ER and OR nurses. In 2016, public sector health-care nurses in Canada worked an estimated 20.1 million hours of paid and unpaid overtime. This number is equivalent to 11,100 full-time positions, with 1,400 of those attributable to BC.

In fact, unpaid nurse overtime in BC averaged 11,300 hours per week in 2016, at an annual value of $21.3 million.

THE HUMAN COST

The correlation between excessive workload and employee burnout is well established. BCNU-sponsored research reveals that more than half our members have cited burnout as the main reason for their intent to leave their job or profession.

Workload factors associated with nurses' dissatisfaction include emotional exhaustion, short-staffing, and a lack of time to complete necessary nursing tasks. Just as important, of those BCNU members who work part-time or casual, over one-third told researchers that they chose to work fewer hours because they felt that full-time work was too demanding.

One in five nurses in Canada leaves their job each year, resulting in enormous turnover costs. This should serve as a serious wake-up call. There's no question that nurses are committed to safe patient care, but there is clear evidence that without the necessary support, they are sacrificing their own well-being in the process.

Governments and health employers have no difficulty proclaiming the importance of nurses and other health-care workers. But to date, investments made have not measured up to the sentiment. It's time for us to put our money and our smarts where our values are.

The statistics that follow provide an overview of the staffing crisis and the changing nature of the nursing workforce.

UPDATE (Dec 2019 / Jan 2020)